Read previous part: iOS 6 Kernel Security - A Hacker's Guide

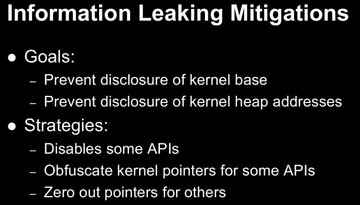

Experts from Azimuth Security now shed light on the goals and strategies of information leaking mitigations for iOS 6, and delve into the kernel ASLR technique.

So, essentially, what they did was they disabled a few APIs. For the bulk of APIs that disclose kernel pointers, they actually obfuscate them. And then there are a few others where they just zero out pointers, where they decided they didn’t need them.

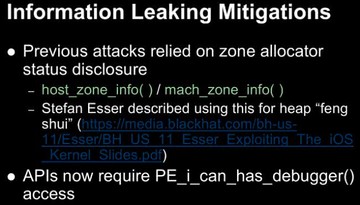

These APIs were particularly useful for heap grooming and stuff like that. Apple of course decided that this wasn’t particularly necessary for users to have. The APIs still exist but they now check if you’ve got the special ‘PE_i_can_has_debugger()’ access, which of course by default you don’t.

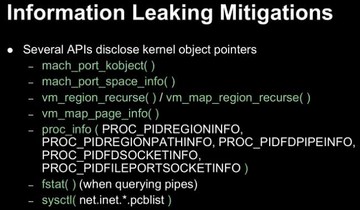

Basically, these APIs are also used internally to some extent by the kernel itself. So they can’t get rid of them – a lot of the pointers, unique values, and things like that. So they still needed them to be unique values, etc. but they didn’t want to give away the kernel pointer. Basically, they just have a simple strategy for obfuscating those pointers, and what they do is they generate a 31-bit random value at boot time and they add that random value to the real pointer, so the structure you’ll read back will have a nonsensical value.

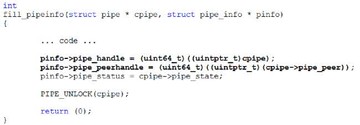

This is an example of structure they used to return beforehand. And you can see this structure, which eventually gets passed back to user-mode, is filling that information about a ‘pipe’, and you can see that the ‘pipe_handle’ value is actually just a kernel pointer; whereas now we’ve got a disassembly, as you can see, they’ve got a random value that they now add to it.

One thing I should mention about this particular example that I chose is, in the latest XNU source code the source code still looks like the one on the previous slide. So, Mountain Lion has actually been lagging behind iOS in a couple of these protections, and some of their APIs are still exposed. I haven’t actually verified on Mountain Lion whether their compiled version is still vulnerable to this particular information leak, but I might do a blog or something where I’ll enumerate the differences that Mountain Lion is still lagging behind and mention them where appropriate. But we were specifically focusing on iOS which has fixed all this stuff.

And then there’s a couple of other APIs that disclose pointers unnecessarily, and so they just zero them out. In particular, there used to be an unknown proc structure information leak using sysctl, and there were some other jailbreaking things used. So they’ve just gone ahead and got rid of that altogether.

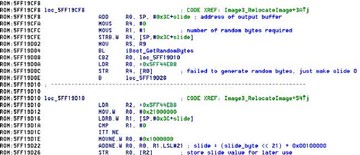

The kernel image is actually randomized by the boot loader before iOS is running. They generate a bunch of random data and then they take a SHA-1 hash of that data; and they take a single byte from the SHA-1 hash and they use that to calculate the kernel “slide”, which is, in effect, the formula that they use to calculate the new base of where they’re going to place the kernel in memory. So it’s basically constant value plus “slide” times 2MB. You can see in the disassembly there – this is actually the code in iBoot that works out where they’re going to load the kernel.

The calculated value that they work out is added to the kernel’s preferred base address, and so, as a result, because they are using a single byte for randomization, the kernel can now be rebased at 1 of 256 possible locations, and the base addresses are 2MB apart. The adjusted base address of the kernel is passed into the kernel in its boot args that iBoot passes to the start function of the kernel, so that the kernel knows where it is in memory.

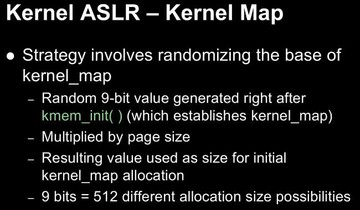

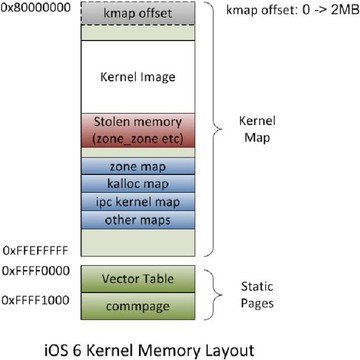

The kernel map basically describes the entire layout of kernel memory. It’s a special map for the kernel task, and basically every allocation that happens within the kernel is allocated from the kernel map either directly or indirectly. Mostly indirectly. Basically, the kernel map spans the entire kernel address space; it starts at 0x80000000 – and goes up to 0xFFFEFFFF. And all the maps that we were discussing earlier, in particular the ‘zone_map’ where ‘kalloc()’ zone maps are allocated, and there’s also an ‘ipc_kernel_map’ and there’s a whole bunch of others – they’re actually carved out of the kernel map as well. So the ‘zone_map’ is like a sub-map of the kernel map.

One thing also worth noting is that the initial allocation that’s at the beginning of kernel memory is silently removed the first time that a garbage collection is issued, which is a process that the kernel does periodically to prune the zones that we were talking about earlier. So the first time that a garbage collection runs they check this if the initial kmap allocation is there, and if it is – they remove it. This behavior can actually also be overridden with ‘kmapoff’ boot parameter.

So, this is an example of how the kernel map would typically look in a standard iOS device. You’ve basically got the random kmap offset allocation at the beginning. Sometime after that you’ve got the kernel image. The stolen memory there refers to some memory that’s manually taken at very early boot time. And then there’s a bunch of zones that happen sometime after that. This is just an example; there’s no reason why zones couldn’t be before the kernel image, if there’s enough space in between the kernel image and the random kmap offset, depending on the random value that was generated through the kernel image when it was loaded. But generally it will look like this.

The other thing to note there is the two static pages in memory: there’s the vector table at 0xFFFF0000, and a shade commpage which is also available in user-mode actually at 0xFFFF1000. These are actually outside the kernel map, so they don’t move.

Read next part: iOS 6 Kernel Security 3 - Kernel Address Space Protection